The warm temperatures that are playing havoc with the Winter Olympics in Vancouver, B.C. have less to do with El Niño than a little-recognized weather phenomenon called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation.

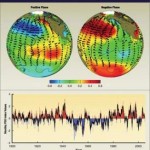

Referred to as the PDO, for obvious tongue-twister reasons, it is an apparent North Pacific temperature cycle. Typically, the PDO causes 20 or 30 years of cooler temperatures followed by 20 or 30 years of warmer temperatures for western North America.

Referred to as the PDO, for obvious tongue-twister reasons, it is an apparent North Pacific temperature cycle. Typically, the PDO causes 20 or 30 years of cooler temperatures followed by 20 or 30 years of warmer temperatures for western North America.

Lately, the PDO has been erratic, but it seems to have joined a rather weak El Niño to create the warm temperatures.

In a post by National Geographic News, a University of British Columbia scientist explains:

“Once El Niño starts, Vancouver typically gets warmer and slightly drier weather,” said William Hsieh, an atmospheric scientist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

El Niño usually peaks in the tropical Pacific Ocean in December and January, but it takes about a month for El Niño waters to travel north to Vancouver’s latitude. “So our peak El Niño effect is around February,” he said—just in time for the Vancouver 2010 Olympics.

Even so, Hsieh said, “This is not a particularly big El Niño, whereas it’s a record [warm] January.” Hsieh said.

The discrepancy may in part be explained by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (or PDO) an apparent North Pacific temperature cycle. Since about 1900 the PDO has resulted in 20 or 30 years of cooler temperatures followed by 20 or 30 years of warmer temperatures for Vancouver and other western North American cities.

In recent years, though, the PDO has been fairly erratic, with fairly short cool and warm periods. The phenomenon had a cooling effect on Vancouver starting around late 2007, but last summer that effect disappeared quite rapidly.

“It sort of appeared to have faded and no one knows why,” Hsieh said. And just as the PDO’s cooling effect sputtered, in stepped El Niño. “That really stacked the deck against us,” he said.